Day 5: A train in Africa

The writing of the next leg of this journey is either going to come spilling out or it's going to stay snuggly tucked inside somewhere. "Day 5" starts the part of the trip that was the best, the most telling: We'd gotten used to motion, bumping from one destination to another, gotten used to one another -- when to talk, when not to, when you need a tissue, when I do. In essence, how to live in a state of travel together.

We waited for the afternoon train at the Nouadhibou Gare. I was trying to get through Out of Africa but finding it hard to reconcile my experiences with hers and preferring my own landscape I put the book away. It was windy and a little hot. We were surrounded by white sand and people spreading their luggage out in circles around them. I watched a little baby boy teeter around barefoot crumbling his bisquit down his shirt, simultaneously watched and ignored by his family. I didn't know at the time but the same baby would travel crying with us all the way to Chinguitti in the far north, to where we would finally spot the "official" desert we were looking for.

The train only comes once a day. It's not even a passenger train, but one for iron ore hauling the mineral from the mines in the north to the port here in Nouadhibou. So we were riding in a just-emptied train, which probably affected the people more who were riding in the back. You see, you can ride for free in the cars carrying the iron ore or you can pay the 2,500 ouigya (somewhere between $5 and $10 I don't remember the conversion) like we did and ride in the sole passenger car. We'd heard stories about the coldness of the ride, how it's dirty, uncomfortable, something no one regrets doing but will never do it again. We were getting in with the least and the most of expectations.

When the train arrived, everyone rushed to mount the small, high stairs into the car. Because that's what people do here (something I've seen in Senegal) rush into transportation as if you have no hope for another, which we didn't in this case. The nicest most genial person turns to a fight-for-a-seat survival skill and in Mauritania that means if your ass is less than five feet wide (mother you don't even know) you're not only pushed to the back of the line, but you will be squashed even if somehow you think you're tough and know a thing or two (like me) and make a dive for it.

The train was a relic of former glory complete with signs posted on the window in three languages not to throw anything out the window (which we did), bathroom signs telling not to smoke (which we did), lights that used to be at every seat and but lighting was now replaced by a candle rigged into a plastic water bottle tied with yarn hanging from the ceiling. What was once, I imagined, sparkling and red was now so gray and dirt clogged that my nails and hands told only half the story of dirt. I wouldn't have traded it for anything.

The same women who butted us off the stairs moments before turned out to be our cabin-mates. Once on, we quickly made for a cabine with women knowing we could find comaraderie (and snacks) and wanting to avoid sitting scooted up next to a sketchy male for 12 hours. In this choice, started our voyage of wonder not once lifting our books or even talking to each other, we sat amazed by these women and the world they created -- world within in a world. A train in Africa. Mauritania. The Sahara Desert. Tsilat's first time riding in a train. Our little cabine seating a young girl maybe three years old, an adolescent boy, and three older, bigger women, mothers for certain possibly grandmothers, capable, strong, submisively veiled head-to-toe, but secretly liberated in their talk, their laughter, their henna-tatooed hands, their seductive dance qu'elles ont montré pour nous as the light got darker and our train headed passively into it. We, too, became one of their command, one of their daughters, handing us food, removing our shoes for us, curling our legs under, touching our hair, smiling and scolding. We did this all without words speaking but not needing words for we had another language: That of women. Of caring, of mothering, of soothing, of protecting.

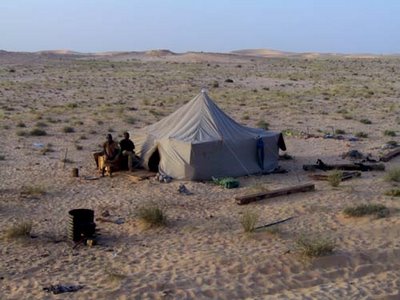

When I needed stretching I sat up and popped my head out the window and watched the small villages, herds of camels, sand dunes, and nothingness come my way, pass, and be gone. I was so wrapped up in it, I didn't need sleep, nor a future, nor a past. My heart just beat with the movement of that train. We stopped at sunrise so the men could pray. I yearned to be one of them. The peacefulness of it. I was worshipping this journey, this land, knowing thyself, and getting called back to our cabine to take la troiséme (third and last round of tea). We stopped two other times to drop passengers off to unknown destinations in the desert. There was no announcement just suddenly motion would cease and we all looked up confused like the world had stop twirling on its axis. We fell asleep sometime in the middle of all laying and propped up against each other limb upon limb and head. Jolted around 3 a.m. to our ladies waking to ask someone in the hall where we were "Choum" was the whisper and we were pushed out into the night bags and butts landing flop in the sand. And it was over. It'd been 13 hours, but somehow I couldn't help feeling I'd wanted it to last forever the sleep, the ride, the present statement, our ladies, our cabine.

1 Comments:

I noticed your big butt comments!! thank you God for the health that goes with it! What a beautiful experience you are having...love mom

Post a Comment

<< Home