Excerpts from a journal entry

16 Oct. 2005 dimanche (Sunday)

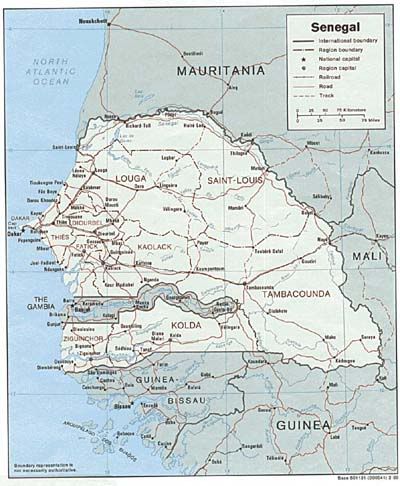

And it was one of those days that, well, I've never had before. Tromping through the north central region of Senegal, bumping along backroads, no roads, and roads that end, looking for a village that used to be called one thing and is now called something else. A Wolof village. A small village which we circled upon circled before finally finding. They remembered the toubabs (foreigners) who were here 10 years ago, "yes yes that was us" (not me of course). Amadou and Gray had been there before to do interviews about the land and had taken photos. This was a return mission to show them the photos. The village chief smiled wildly recognizing himself in the first photo. The women grabbed the rest, some were small in the photos, some weren't born yet. And many had died or departed.

The conversation in Wolof with Gray as my little English bird translating some words and Amadou stopping to take notes and translate to us in French. Conversations about the four young people from the village who've left for Italy, others who've left for Touba (a larger, religious city in Senegal) and of course for Dakar. And conversation on how they are only using about 10 percent of their cultivatable land for crops, planting sorghum, millet, bissap, peanuts.

Driving... loved the endless and always remarkable and always unique croppings of baobabs. Loved learning the vegetation which, if I'll remember, is somehow satisfying -- satisfying to look out into a land and know its trees. Hmmm what do I know so far? Desert fig, umbrella tree, winter thorn, neem the fast growing shade tree (sp?).

Sweated more than I ever have before even the hot wind through the windows was infernal. The Dakarois who said it would be hot were right "il fait chaud." Ate a Senegalese watermelon and mandarin. The mandarin tangy and only a little sweet tasted as fresh as it can be. Watermelon ate so much of since there was no way to keep it for later.

And now I'm lying in a cot beneath the stars, the temperature has cooled to a perfect degree, and I'm in Senegal, in it for good.

See some more photos here