Circling the Baobabs

The homestretch

Thursday, April 27, 2006

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

Day 7: Going further

In a whisper the day before, as I was gulping down a meal of rice and carrots and specks of sand, Cheikh the patron of our auberge spoke about arranging a guide to take us into the desert with camels. I told him that's why we're here. We arranged a price using for our bargaining chip that we were nearly out of ouguiyas and with no way nearby to change money. We made our plans to leave at dawn.

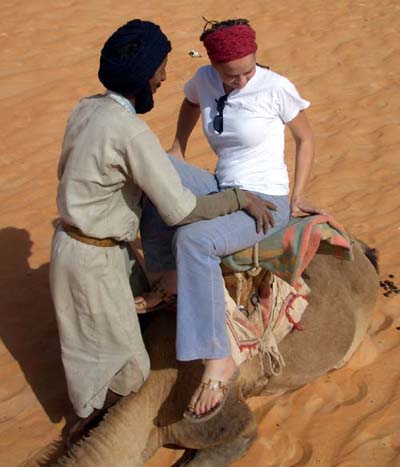

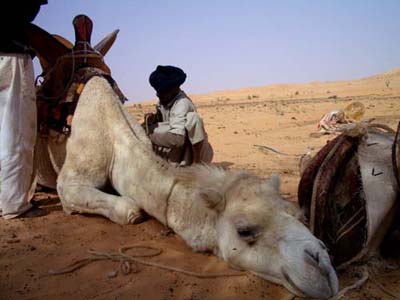

The next morning our guide arrived with our saddled camels. We walked first to the outskirts of Chinguitti. It was a slow start with the sun already hot and trying to reign in my excitement and marathon my energy. When got far enough, we mounted our camels and set off into the indisinguishable distance.

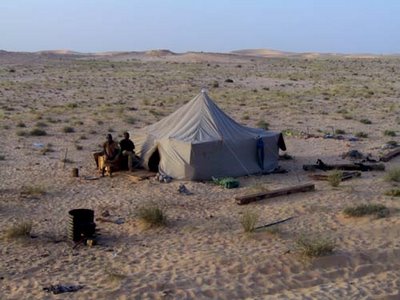

The farther out we got I realized the weight of what it is to be engulfed, to circle and see only dunes, to breathe and smell nothing, to marvel at the sands changing colors and the few scrappy trees. I gave myself up to one more mass of nature hoping only I'd come out at the end maangi fii the blankets of sand, the non-stopping heat, the wind whipping at our feet covering our tracks, all roads lead in and none lead out. Every detail was highlighted to micro -- the indent made by the trail of our prints, the falling sand off the tip of a dune, the way the wind whipped and layered the earth in even aligned paths of sandy color and design. I could stare at a single point in the distance as we padded towards it on our camelbacks and to never arrive at it, the distance seemed always to be in the same spot -- far away. We were moving without moving. But we must have eventually got somewhere, because by day's end we did make it: A date oasis surrounded by a small village of four families.

We were greeted by women, a deep well of cold water, and a cluster of tall and shady trees. The place exuded coolness that only a place a day's journey from anywhere could in the middle of an infinite ton of hot sand. The smell was watery, soil-fied, a greenhouse. I descended with the strongest yearning for a cold bottle of Fanta almost physically hurting Tsilat by voicing my desire. It'd been a hot journey and long and our water was warm enough to seep tea. When one of the veiled Hassinya women came towards us carrying a bucket, she lifted the lid to four cans of Coca bobbing in a pool of cool water. Even if I could have spoken to her, I don't know what I would have said. She just edged it towards us and I gasped at the feel of Coke in my throat.

I disappeared to watch the sunset. Atop a dune, I buried my legs in the sand -- cold if I reached way down. The quiet's like coming outside at night after a snowstorm in South Dakota where there's only calm, the roads not yet plowed, the snow sits where it lands and nature has the upperhand until morning when people wake and sidewalks are shoveled and roads are tracked by traffic. I let a lot go at that moment spreading my Dakar-braided head on the mat of sand staring at the darkening sky and feeling the desert.

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

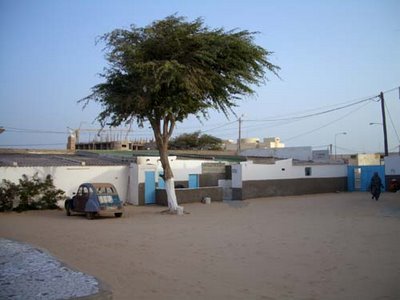

Chinguitti: A city of sand

"The sand closes in on you in Chinguitti. An ongoing project by the European Union to haul sand out of the streets back into the desert leaves less than before, but I still feel it casacading in. The roads are soft, fine desert sand. Houses are made of sand/water combination. I'm buried in a sand castle here and it's easy to feel like time is in the middle between ending and beginning and I'm being pushed through the wings of an hourglass spat out and turned into rosy-colored mud." - Journal entry

We padded around the city in the late afternoon just as the sun was setting. It was much too hot to come out of our tents during the mid-day sun -- finally we were getting some real desert heat. It's a city with some running water, electricity only between the hours of 8 and 10 p.m., and a couple of phone lines. However sparse, it houses one of the largest collections of manuscripts written by the Prophet Mohammed in the 600s (supposedly since this is all somewhat debatable). It's considered the seventh holy city of Islam -- but as one peace corps volunteer put it: what's the eighth city?

It felt quaint as desert towns go. The sandy walls of the hundreds-years-old buildings still tweeter with the old tale that Chinguitti was once located a little farther to the north but it was buried in sand and so another city had to be re-started here. Our volunteer told us of prejudice he faced for not being Muslim -- some people in the city refusing to talk to him making it seem that perhaps sand is not Chinguitti's only enemy, but maybe the outside world. I'd heard the farther north you get in Mauritania the more devout the Muslims and the closer you get to Senegal the more "Christian" sarcastically speaking since Senegal is at least 95 percent Muslim, it's just some consider the form of Islam here diluted.

But we were two girls smoothed with travel intent that our path would take us where we wanted to go. The afternoon sun went setting and we trodded through the thick, heavy sand like it was a dance. We found a baayfall Senegalese vendor named Boubacar selling trinkets he offered to make us a good cup of homebrewed ataya (tea) instead of that weak sh*t they make here in Mauritania. We brazeningly said goodbye laughing that we were off to the desert tomorrow morning and he asked at the heart of our laughter: "What desert? This is the desert." Desert, yes, but we must get farther out and my faced turned to serious, out there I point to the now-not-so distant dunes -- we're going there.

Thursday, April 20, 2006

Day 6: I saw the sunrise over the Sahara

After getting dropped off in the middle of the desert sometime in the early morning my contacts dried to my eyes from sleep and my head whirrling from the stillness, we piled into a small Toyota truck and took off slowly down a path through the open space. The other people in the truck were a Mauritanian businessman who spoke French, Arabic, and English and his manservant; two French tourists (a man and a woman); and in the bed of the truck seven or so Senegalese/Mauritanian men riding on top the luggage. I remember being squeezed into a back seat with three others and looking out the window to see only the hole of the headlights in front of us and thinking this is the craziest thing I've ever done I couldn't even have found myself on the map at that moment much less made my way to the next city on my own. And then I fell asleep my head bobbing from the jostle of the road. I dreamed about taking this trip with my brother, and I woke up to the now-familiar sound of flapping rubber. We stopped and a guy motioned for me to get out of the car -- I'd been so comfortable in my cacoon that I wasn't quite sure how to descend. In the time it took to change the tire, the sun slowly started to wake up, to se reveiller. The muslims took out their prayer mats and started praying towards that distant light and I slowly dropped to the ground. It's amazing how the two are so distinctly separate -- sky and land -- at this moment. I know surprise has been expressed about how this could happen every single day-- and we notice it not. It was a miracle to me to be at this place at this time watching the light and those men pray towards it. Again I would have become one of them, just to be sure of something, just to give myself to something, just to say thanks, just so I wouldn't have fight not knowing.

When were dropped in the city of Atar sometime around 8 in the morning. The taxi took as to a small auberge and we used their bathrooms to wash and then we sat down for breakfast with the French couple. They wanted to bargain for a taxi to take us around the various oasis in the area and wondered if we'd go along. The price seemed reasonable but it would have been two days non-stop travel, and we didn't want that, so we backed out and decided to take a taxi brousse to Chinguitti, the city about an hour north of Atar where we could really see desert and play in the sand.

At this point, the landscape though desert-ified wasn't the sand dunes we were craving to set our eyes upon. As soon as we left Atar, I was surprised by the rockyness of the landscape, the tall-tall almost mountains and the yellow flowered fields. It was soon that we crossed out of this and into the sand.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Day 5: A train in Africa

The writing of the next leg of this journey is either going to come spilling out or it's going to stay snuggly tucked inside somewhere. "Day 5" starts the part of the trip that was the best, the most telling: We'd gotten used to motion, bumping from one destination to another, gotten used to one another -- when to talk, when not to, when you need a tissue, when I do. In essence, how to live in a state of travel together.

We waited for the afternoon train at the Nouadhibou Gare. I was trying to get through Out of Africa but finding it hard to reconcile my experiences with hers and preferring my own landscape I put the book away. It was windy and a little hot. We were surrounded by white sand and people spreading their luggage out in circles around them. I watched a little baby boy teeter around barefoot crumbling his bisquit down his shirt, simultaneously watched and ignored by his family. I didn't know at the time but the same baby would travel crying with us all the way to Chinguitti in the far north, to where we would finally spot the "official" desert we were looking for.

The train only comes once a day. It's not even a passenger train, but one for iron ore hauling the mineral from the mines in the north to the port here in Nouadhibou. So we were riding in a just-emptied train, which probably affected the people more who were riding in the back. You see, you can ride for free in the cars carrying the iron ore or you can pay the 2,500 ouigya (somewhere between $5 and $10 I don't remember the conversion) like we did and ride in the sole passenger car. We'd heard stories about the coldness of the ride, how it's dirty, uncomfortable, something no one regrets doing but will never do it again. We were getting in with the least and the most of expectations.

When the train arrived, everyone rushed to mount the small, high stairs into the car. Because that's what people do here (something I've seen in Senegal) rush into transportation as if you have no hope for another, which we didn't in this case. The nicest most genial person turns to a fight-for-a-seat survival skill and in Mauritania that means if your ass is less than five feet wide (mother you don't even know) you're not only pushed to the back of the line, but you will be squashed even if somehow you think you're tough and know a thing or two (like me) and make a dive for it.

The train was a relic of former glory complete with signs posted on the window in three languages not to throw anything out the window (which we did), bathroom signs telling not to smoke (which we did), lights that used to be at every seat and but lighting was now replaced by a candle rigged into a plastic water bottle tied with yarn hanging from the ceiling. What was once, I imagined, sparkling and red was now so gray and dirt clogged that my nails and hands told only half the story of dirt. I wouldn't have traded it for anything.

The same women who butted us off the stairs moments before turned out to be our cabin-mates. Once on, we quickly made for a cabine with women knowing we could find comaraderie (and snacks) and wanting to avoid sitting scooted up next to a sketchy male for 12 hours. In this choice, started our voyage of wonder not once lifting our books or even talking to each other, we sat amazed by these women and the world they created -- world within in a world. A train in Africa. Mauritania. The Sahara Desert. Tsilat's first time riding in a train. Our little cabine seating a young girl maybe three years old, an adolescent boy, and three older, bigger women, mothers for certain possibly grandmothers, capable, strong, submisively veiled head-to-toe, but secretly liberated in their talk, their laughter, their henna-tatooed hands, their seductive dance qu'elles ont montré pour nous as the light got darker and our train headed passively into it. We, too, became one of their command, one of their daughters, handing us food, removing our shoes for us, curling our legs under, touching our hair, smiling and scolding. We did this all without words speaking but not needing words for we had another language: That of women. Of caring, of mothering, of soothing, of protecting.

When I needed stretching I sat up and popped my head out the window and watched the small villages, herds of camels, sand dunes, and nothingness come my way, pass, and be gone. I was so wrapped up in it, I didn't need sleep, nor a future, nor a past. My heart just beat with the movement of that train. We stopped at sunrise so the men could pray. I yearned to be one of them. The peacefulness of it. I was worshipping this journey, this land, knowing thyself, and getting called back to our cabine to take la troiséme (third and last round of tea). We stopped two other times to drop passengers off to unknown destinations in the desert. There was no announcement just suddenly motion would cease and we all looked up confused like the world had stop twirling on its axis. We fell asleep sometime in the middle of all laying and propped up against each other limb upon limb and head. Jolted around 3 a.m. to our ladies waking to ask someone in the hall where we were "Choum" was the whisper and we were pushed out into the night bags and butts landing flop in the sand. And it was over. It'd been 13 hours, but somehow I couldn't help feeling I'd wanted it to last forever the sleep, the ride, the present statement, our ladies, our cabine.

Friday, April 07, 2006

The story of Nouadhibou is a way to get to Europe

A place where desert meets ocean.

Look around you, if you don't see African faces in your neighborhood, you will. If you want to continue to ignore the drought, the desertification, the poverty, the wars, the corruption of Africa, it will come to you, smack in the face through riots in Paris or the immigrants landing wide-eyed and sweat-stained in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I'm only saying it because it hurts to know if the going gets tough I can fly outta here anytime I want, but my good friends living here, can't. Together we sit on the beach staring out at the ocean watching the planes fly in close and low -- I know what it feels like to be on one o' them, I know where it takes me, but do you? I can love this place and these people, but I can never really invite them chez moi. And yet I stutter as I weigh what I'll do in the future tip toeing between finding work at home, mooching off my family for a few months, staying in Senegal, or finding another reason to take me overseas. I may not be an American who likes Big Macs and Cokes, but I am one who constantly revels in the choices, and yet my friends here can't even find one single job. But coming where I come from means I will always find work, I will always go to school, always have money and food and a place to live. It makes you wonder how to define a human right. The right to change my mind ten thousand times?

Taking in the spray of the ocean.

And that's what Nouadhibou did to me. Made me feel and question and instead of marveling at why someone would be crazy enough to take a three-day pirogue ride into the ocean, I wondered what's pushing someone to even consider it. But even as I write of the "conditions of Africa" I chide myself because there is so much good here and even in its direness, there are the people who smile and greet you like no other day is a comin' and businesses that succeed and people who make it. I guess there's no real way to grasp the whole picture and I'm flailing only to understand a small part of it, my part in it.

Monday, April 03, 2006

Day 4: gnarled twists of fate

We slowly prepared ourselves for a day of travel -- this time, north to the desert. Knowing water and showers would be scarce, we took our time with the precious drops of hot water and toiletries and clean shirts. We got our instructions on where to go and who and how, hugged Molly good bye promising to see her in a few days, walked to the street and hailed a taxi. And this is when we had a strange turn of luck...

The other thing about taxis in Nouakchott besides being Mercedes is most of them are driven by Senegalese who come here looking for work. I greeted him in Wolof and asked him to take us to the Garage Atar, where we'd get the cars to Atar, the city in the far north that's the setting-out point for most desert voyages. We got to the garage and a gendarme (police man) approached our car, the driver negotiated our price with him, we were showed our taxi, paid and quickly left town. After we'd been in the car for awhile I started talking to the Senegalese guy next to me, something that wasn't too difficult since we were practically ear-to-ear and I was half sitting on his lap asking myself how I could get this close and personal to a men I hadn't yet met (after we'd left the garage we'd pulled over to squeeze one big-butted Mauritanian woman into the backseat of our car -- making us four in one standard size backseat for three). I asked him what he was doing in Atar and he said he was going to Nouadhibou to visit his family. It dawned on me a little then and I wondered why we were going towards Nouadhibou, a city on the coast, far from the desert. I saw signs on the road counting down the kilometers to Nouadhibou and still I thought eventually we'd veer off for Atar, that somehow the road would split and this guy would get out and go one way while we went the other. When three hours later we started driving alongside the ocean, I knew we weren't going to be spending the night in the desert, so I mentioned it to Tsilat, "I think we're going to that city where Mark lives." Mark being a peace corps volunteer we'd met in Dakar and "that city where he lives" being Nouadhibou which I hadn't yet learned to prounounce. Somehow the taxi driver had negotiated us a ticket to Nouadhibou and not to Atar. So much for speaking Wolof to taximen.

Since this is where we were, we decided to make the best of it and try to track down Mark. We took a cab into town, found a chill place to hang out and get some food, read our travel book about Nouadibou, tried calling Mark but he didn't answer. We checked in to a tiny auberge -- one narrow room, two beds on the floor. You could rent a mat in the tent if you wanted or even the old car in the courtyard to sleep in, but we opted for the room, as yet our skin hadn't constricted tight around traveling rough (that would come later), still valuing showers in the morning, clean clothes every day, and a semblance of a room over our heads -- at least one held up by a door that locks.

It was strolling around the streets of Nouadibou that we came into our own. It's a city on a narrow peninusula into the ocean with half of the peninsula being the territory of the Western Sahara (or Morocco however you look at it). Largely unpestered we wondered aimlessly through neighborhoods and markets looking into people's homes, shops, and anybody's business. That's the way it is here (here as in the Africa I've seen), everything that is done is done for the world to see. It's only the rich and the toubabs with something to hide or something to show who lodge themselves behind walls and guards and locked gates. I was surprised we weren't followed. In Senegal, I can't step out of the house without acquiring an admirer or two, especially when I venture into tourist places, men wanting to be my guide, to sell me a drum or a wooden statue a beaded necklace an African mask, and always to me marier. I was surprised by the busy-ness, the kids whizzing by on bikes chasing each other not giving us a moment's pause. In America, you see kids on bikes. In Senegal, jamais never. And nearly everwhere I looked -- shacks, stores, street corners -- people were clustered around a boiling pot of tea -- and we were offered it at every turn and we sipped it and we talked and it was polite and cordial and not whacking you in the face the way Dakar has a way of doing. Again, I was feeling the calm.

We finally reached Mark, who'd been having problems with his cell service, by calling another peace corps girl who'd been in his apartment before him and led us phone-to-door and it was warmth and smiles to see someone familiar. Mark entered peace corps late in his life compared to most of the bitties who prefer to find themselves straight out of college fleeing from desk jobs and unadventure. Mark was in business in Boston and still has that sense about him even all the way over here. He speaks French with his Boston accent and has a calm capable manner, always respectfully hearing someone out. He teaches English to classrooms of high school students and night classes to adults, which as we walked the streets with him, constantly brought on greetings by kids smiling to clamor out their how are yous.